Preserving Resistance Movements in Digital Toolkits

The grassroots energy that animated the civil rights movement catapulted it into one of the most significant markers of pursuits of democracy in America in the 1960’s. Judy Richardson describes her current work as a continuation of that movement.

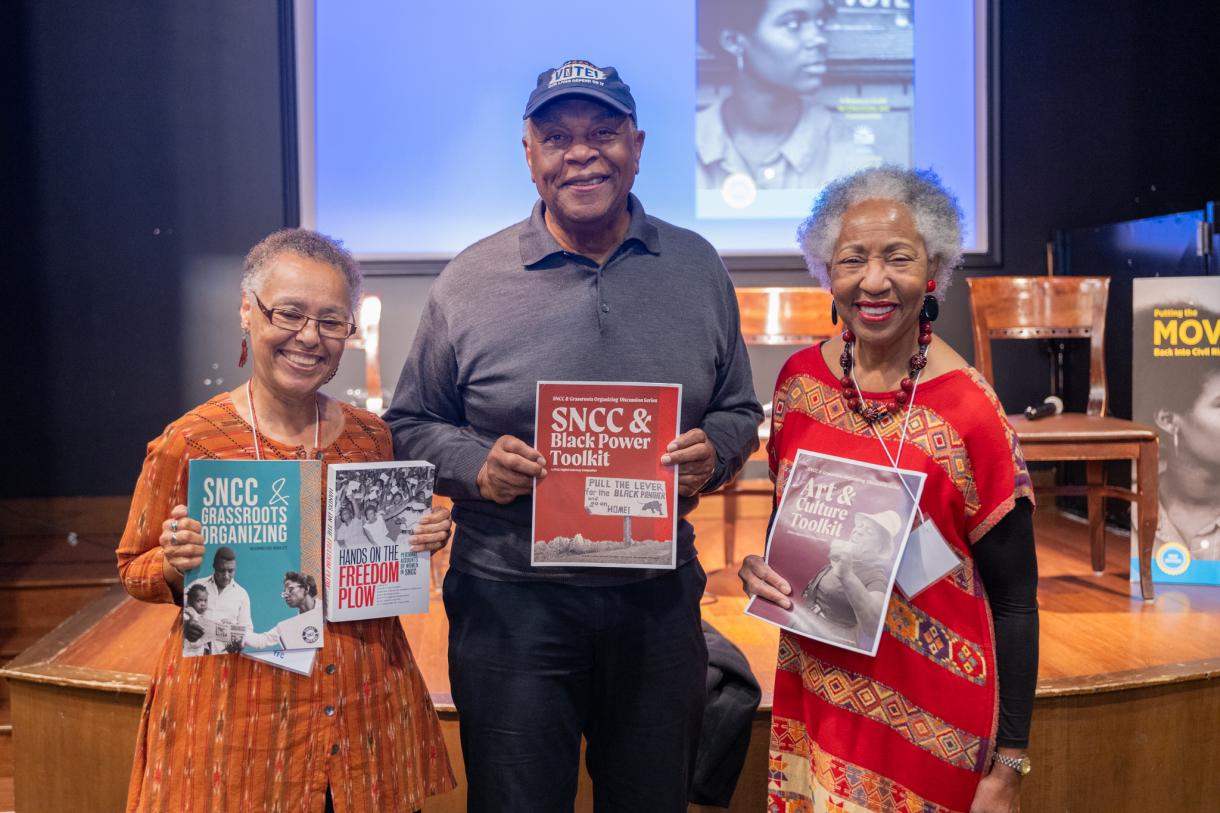

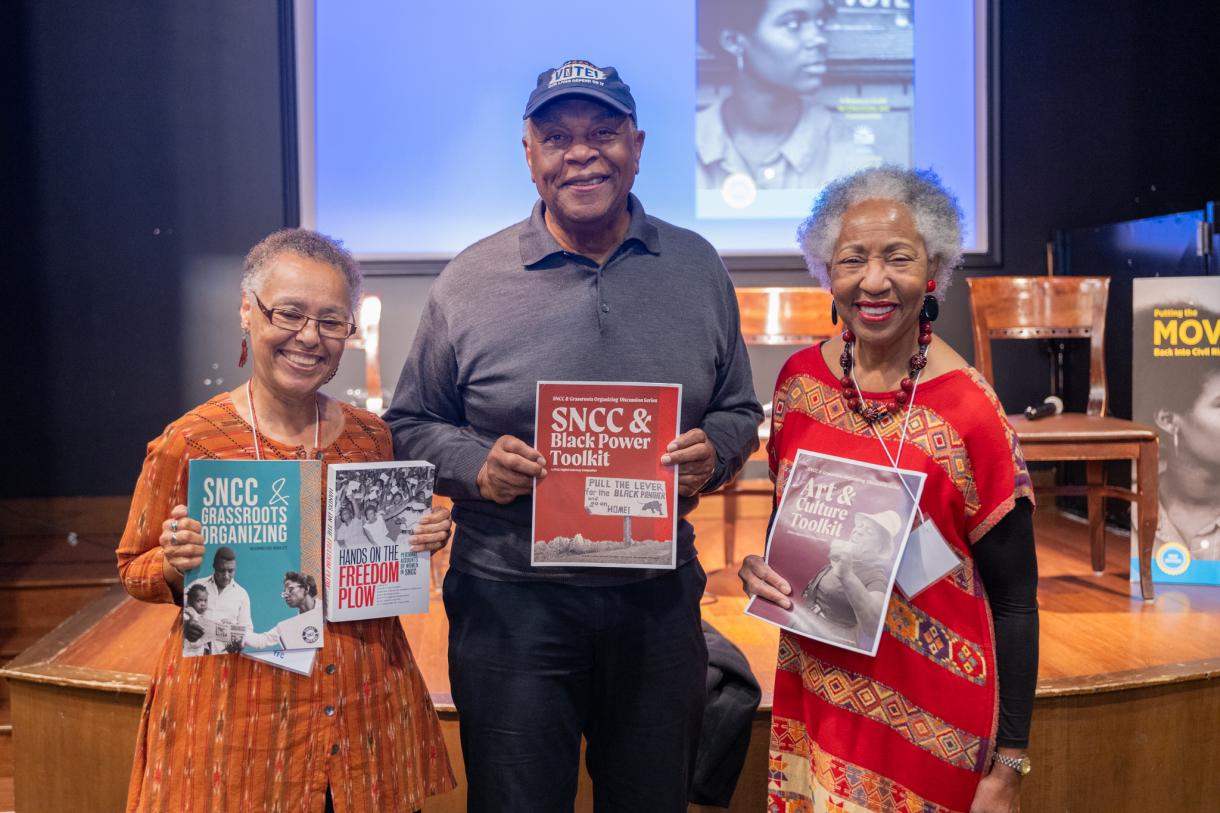

A veteran of the legendary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Richardson serves on the editorial committee for the toolkit portion of a project known as SNCC and Grassroots Organizing. SNCC was among the most visible youth-led organizations in the 1960s southern civil rights movement.

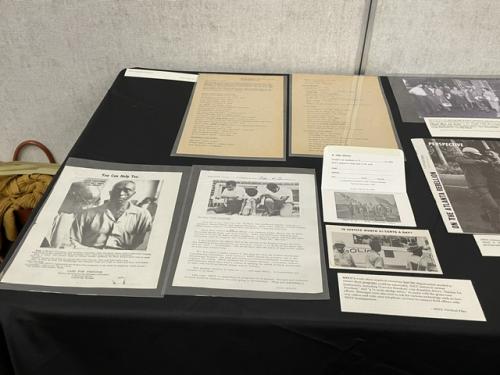

The project is a concerted group effort that makes the deliberate strategies, personal narratives, and organizing lessons of SNCC more accessible to new generations of educators and researchers, as well as students and community organizers.

“When I was working on the 14-hour PBS series Eyes on the Prize, I had the sense that I was expanding my movement work with SNCC. And that’s how I see this toolkit,” Richardson said. “It’s an expansion of the kind of movement work and organizing we all did in SNCC.”

The toolkits are part of a larger multimedia documentary project hosted by Duke University that includes the SNCC Digital Gateway. The kits are ultimately designed to work in tandem with the website, telling SNCC’s history from the inside-out and bottom-up.

Developed in partnership with six historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), its collaborators include North Carolina Central, Howard and Tougaloo, as well as six African American history museums, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the civil rights museums in Memphis, Birmingham and Jackson.

Each toolkit focuses on one of 6 themes, from Freedom Teaching, Art and Culture, Women and Gender, and Black Power, to the Organizing Tradition. All highlight firsthand accounts from SNCC organizers and the community members they worked alongside.

“What it focuses on is who we were, what we did, and why we did it,” Richardson explained. “Because the ‘why’ is really important.”

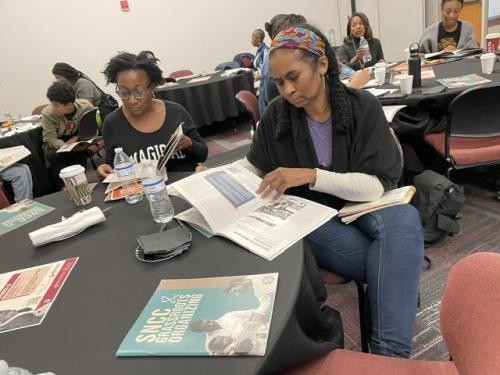

The toolkits are intended to reach individuals outside of academia and serve as a link between history and practice. “We assume that the main people coming to this site are regular folks,” she said. “They are community members and organizers—maybe they run a freedom school in their neighborhood.”

For Richardson, the goal is to demonstrate the continued relevance of the shared leadership, coalition-building, and local grassroots empowerment tenets that shaped SNCC’s organizing work in the 1960s.

“A lot of those things can be used now in terms of the struggle we’re in,” she shared.

Its ongoing relevance is demonstrated by the project’s link between the movement’s veterans and present organizers. Young activists from groups like Dream Defenders and BYP 100 continue to collaborate with the SNCC Legacy Project.

“It’s not us just telling them what to do,” Richardson said. “It’s a synergy. We stay in conversation with young people who are on the ground doing grassroots organizing.”

Preserving that intergenerational dialogue is crucial not only for sharing this history, but also for sustaining collective strength. “We were the only youth-led and youth-started organization within the Southern movement,” she said.

“We weren’t fearless, but we didn’t allow the fear to make us dysfunctional, and we surrounded ourselves with other people who thought we could change the world.”

To help young people “see themselves in the stories we’re talking about,” Richardson urges SNCC organizers to to show archival photos of themselves from those years, to remind younger audiences that “we were their age when we were working for social and economic change.”

Ultimately, the project hopes to dispel myths regarding the civil rights era. Richardson highlights that SNCC’s efforts relied on local leaders who mentored and shielded the younger organizers, such as Ella Baker and Amzie Moore in Mississippi, whose networks and ideologies influenced the organization’s strategy.

“In these toolkits and on our SNCC Digital website, we don’t just focus on the work of the young SNCC workers,” she said. “We highlight the older people in those communities who guided and guarded us. We’re also trying to correct the traditional narrative that it was only men, or only Dr. King. There were many “regular” people who made and sustained the movement.”

According to Richardson, the work is equally focused on the present and the future we can build, even as it records vital history. She talks passionately about the present dangers to democracy and the necessity of organizing to preserve and expand what was accomplished during the Civil Rights Movement.

“You’ve got to surround yourself with people who really do think you have an obligation to do something,” she said. “It’s too hard otherwise.” For her, that fostering of community—and the conviction that people can act collectively to change their world—remains SNCC’s enduring lesson.

“The question is always how to get the learning we received from those who passed it on to us into the hands of people now,” Richardson said. “So they can adapt it, expand on it. The point is, if you do nothing, nothing changes for the better.”