Student Spotlight: Trisha Santanam on Literature, Music and the Power of the Humanities

The John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute has worked closely with undergraduates and graduate students across our various interdisciplinary programs and projects. This week’s spotlight focuses on the work of Trisha Santanam, a Duke University senior studying English and Music, and whose critical and creative encounters with both genres extend into new forms of communication.

You can read more about her research endeavors below:

Do you ever find yourself analyzing contemporary music in the same way, or do you try to separate that critical part of yourself?

It’s very difficult sometimes for me to separate the part of me that is thinking critically about music when I’m just trying to listen to a song that I enjoy. But I actually think that maybe that is the task—that we should reduce the distance between the part of us that thinks we have to be critical and the part that experiences enjoyment.

Enjoyment and actually feeling something might be what we should be doing as academics. So I try not to be too hard on myself when I see myself slipping into thinking critically about something I enjoy—because I actually think that’s a plus. It means I’m authentically drawn to what I want to be writing about and studying.

What are your plans after graduation?

After I graduate, I hope to enroll in a Ph.D. program in English or American Studies, continuing to focus on 20th- and 21st-century American literary and musical texts.

I’m interested in being a professor for a variety of reasons. Over these past few years at Duke, I’ve developed a lot of questions about the side of being human that ask us to move through the world bearing sorrow and joy at the same time while thinking about other people. I hope to unravel those questions further through the study of literature and music.

I want to be the kind of professor who provides students with a framework to understand what music and literature reveal about themselves and others—not to train them to think in a certain way, but to show them a path to appreciate the parts of art that are unquantifiable and inexplicable.

I’ve been very lucky to have incredible professors here at Duke who have nurtured not only my conceptual approach to the humanities but also my being and becoming as a human beyond the classroom. I hope to give back to other academic communities what I’ve so generously received as a student.

You’ve collaborated with the FHI through Bass Connections and other programs. Can you tell us about that work?

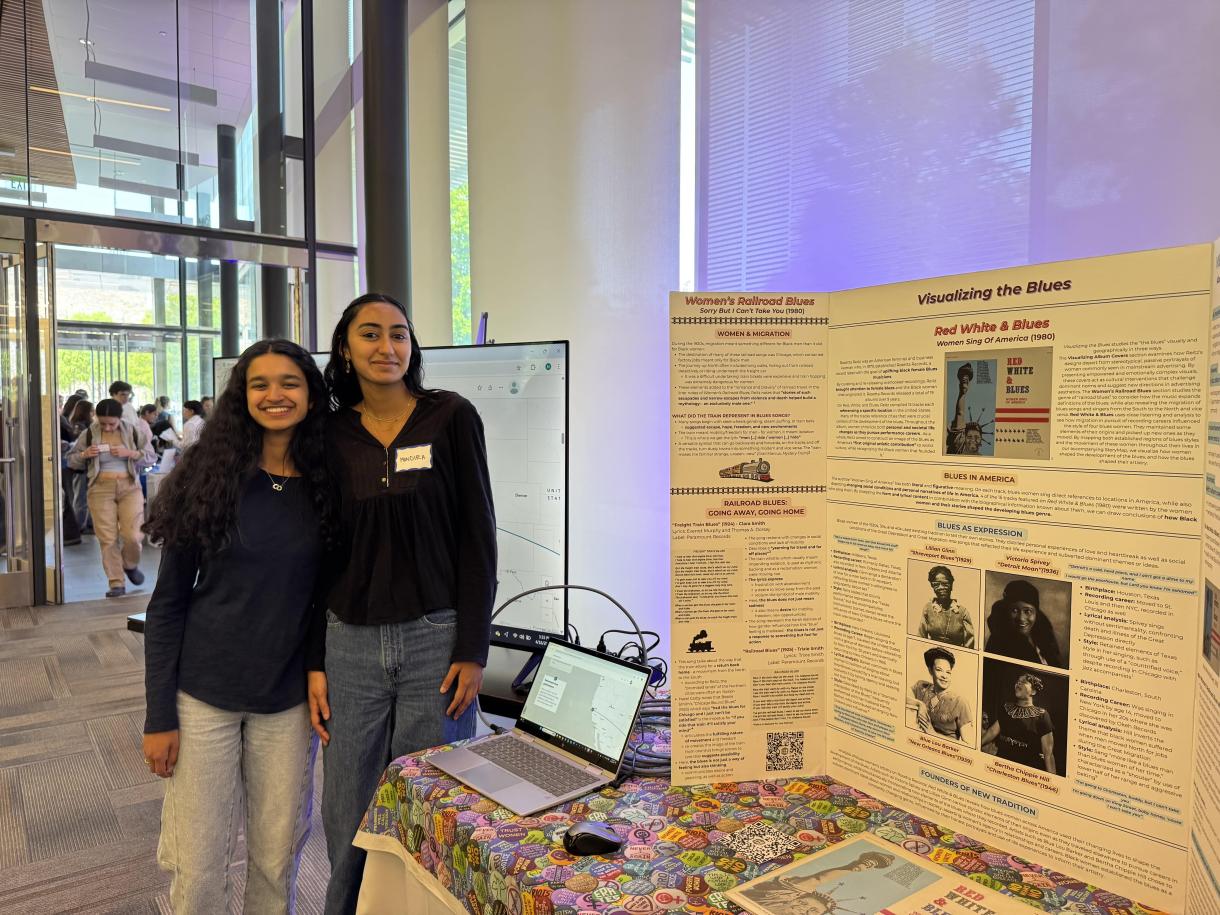

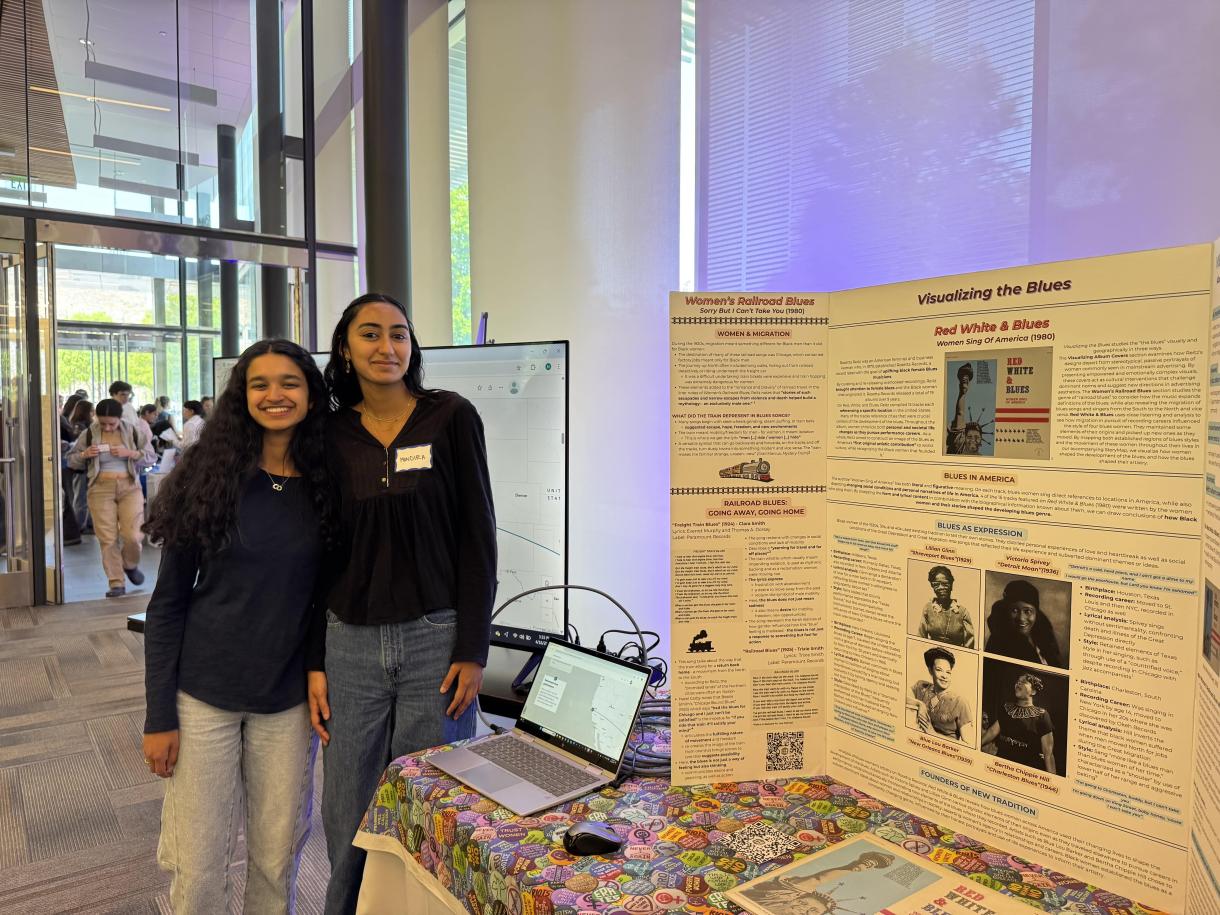

I’m part of the Rosetta Reitz’s Bass Connections project, which relates to my interest in exploring how music is a site of both contradiction and possibility.

I’ve spent endless hours pouring over archival materials from Rosetta Reitz—a 20th-century Jewish feminist writer, business owner, and record and concert producer.

The first event I worked on with the FHI was Sex, Race, and Sweet Petunias in April 2024, with Tift Merritt, Rissi Palmer, and another student, Lindsay Frankfort. We focused on the album Sweet Petunias and each took a song to discuss what it revealed about being a Black female artist at that time—singing the blues, navigating the music industry.

I focused on a song called “Sweet Peas,” looking at how it could be heard and read through the lens of the Victorian practice of floriography—which suggests that flowers have multiple meanings that don’t invalidate each other. Using that method, I expanded understandings of Victoria Spivey’s personal and professional relationships, and argued that conceptualizing the blues women on the Sweet Petunias album as flowers invites listeners to place value in their performances beyond their stage presences.

That connected to a larger ethics of care—an idea that revising the stories told about blues women is a form of caring for important figures who’ve been obscured by the music industry.

What do the humanities mean to you, especially beyond the academic space?

As a humanities student, I remind myself that my task—as both a student and a human in the world—is to refuse to give in to this growing addiction to quantitative data, determinate meaning, and binaries. There’s value in things that resist simplification and insist on being mysterious.

The humanities show us that our lives are full of contradiction, and we should be moving toward that, not away from it. Studying the humanities isn’t just about learning to pass aesthetic or normative judgments about art; it’s about making the strange familiar and the familiar strange.

The humanities allow us to explore the complicated experience of being human—and they have a whole life beyond academia. They open our minds to different ways of looking at and being in the world.

For example, when I was doing research this summer, I spent time in the archives but also in New York City — going to blues and jazz performances, walking around, listening to the music of the city. I realized how important it was to feel what I was researching.

My high school English teacher once told me that art can be unsettling because something real transpires and is disclosed for others to engage with—and that truth, while often uncomfortable, validates the authenticity of our own lives.

The humanities remind us of our capacity to feel, not just to analyze. And they show us that feeling is a different and valuable mode of experiencing the world.